References

The Aberrant Canine Part 2: Treatment

From Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2018 | Pages 6-12

Article

The permanent canine usually erupts uneventfully, but occasionally it may fail to do so. When this occurs there is a potential for the adjacent teeth to be damaged. Even when it does not cause any damage, treatment of the ectopically positioned canine can present a substantial challenge to the orthodontist. Part 1 addressed the aetiology and diagnosis of the aberrant canine. Part 2 will discuss the various treatment options for the aberrant canine tooth.

Treatment of the aberrant canine

Following clinical and radiographic investigations, treatment decisions can be made based, not only on the type of malocclusion, but more particularly on the presenting features associated with the aberrant canine. It is the management of this canine that will now be described.

Treatment for the developmentally absent canine

The treatment options for the developmentally absent canine are either to accept the resulting malocclusion, to reopen the space prior to prosthetic replacement, or to close the space.

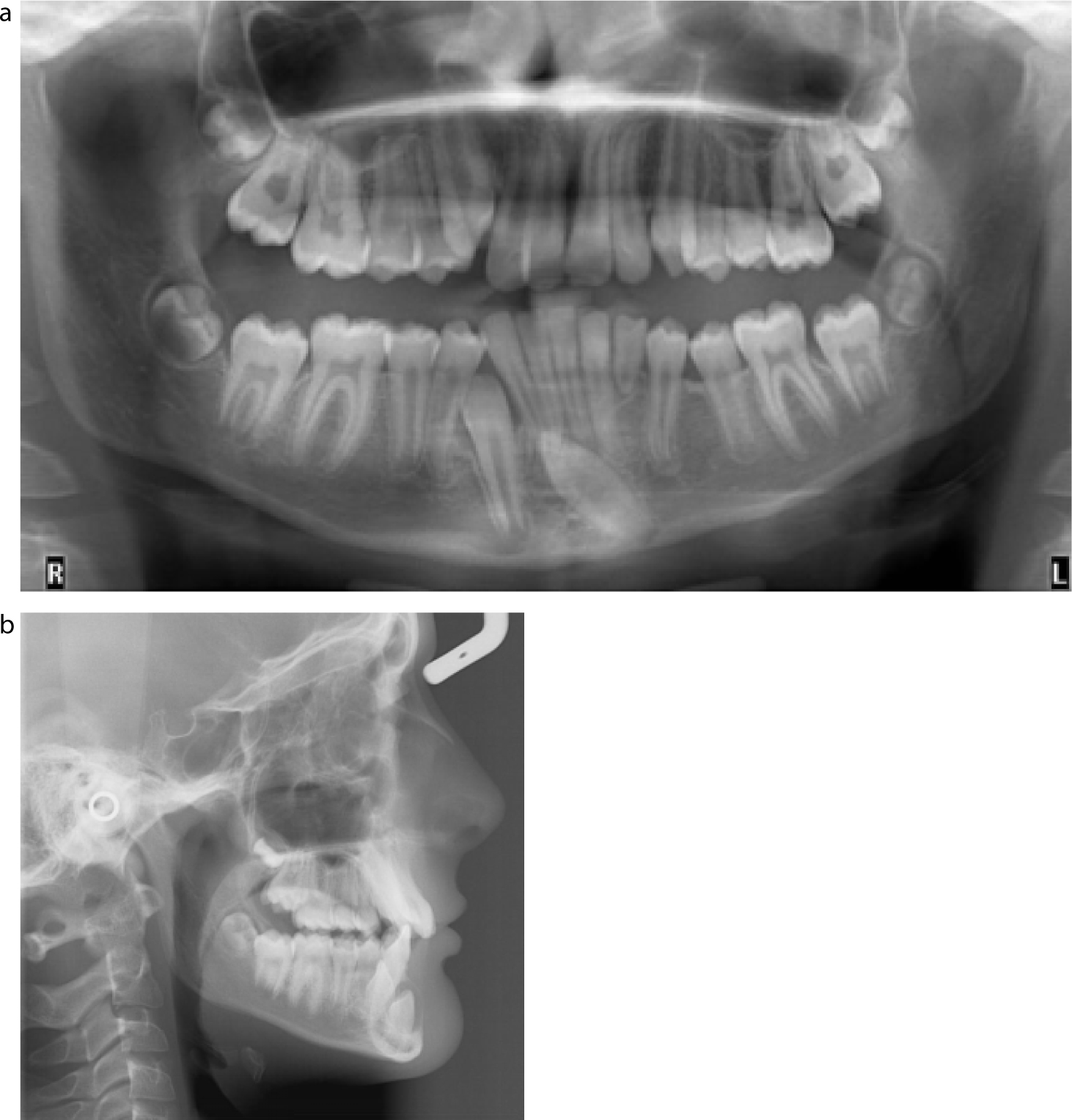

Space closure may be prudent, especially if a good contact can be made between the lateral incisor and first premolar, which is not always possible in the lower arch. The first premolar can provide an aesthetic camouflage solution for the missing canine, but in the upper arch may require buccal root torque, mesial rotation and selective grinding of the palatal cusp to achieve the desired aesthetic outcome (Figure 1).

Treatment of the impacted unerupted canine

When the canine is present but unerupted, there are again a number of different treatment options available, ranging from accept and monitor, through to simple interceptive procedures and, finally, more complex orthodontic treatments.

Accept and monitor

If the canine is extremely ectopically positioned it may not be wise to attempt alignment as this is likely to be a lengthy and challenging treatment for both the patient and the orthodontist. The risks of treatment may also outweigh the potential benefits. If the unerupted canine is left in situ, it should be monitored with a radiograph every couple of years, as there is a risk of resorption of the roots of the adjacent teeth (up until 14 years of age) and, less commonly, cystic change within the follicle of the canine.

Cystic change within the follicle

A rare complication (0.4%) of leaving an unerupted tooth in situ is the risk that the follicle undergoes cystic change.1 In a study by Mourshed,1 cystic change was defined as a visible pericoronal space within the follicle, larger than 2.5 mm in diameter on radiographic imaging. If there are signs of cystic change, the canine should either be removed or aligned within the arch. If left untreated, it can lead to the canine becoming more ectopically positioned or result in movement of adjacent erupted teeth.

Resorption of adjacent teeth and subsequent treatment

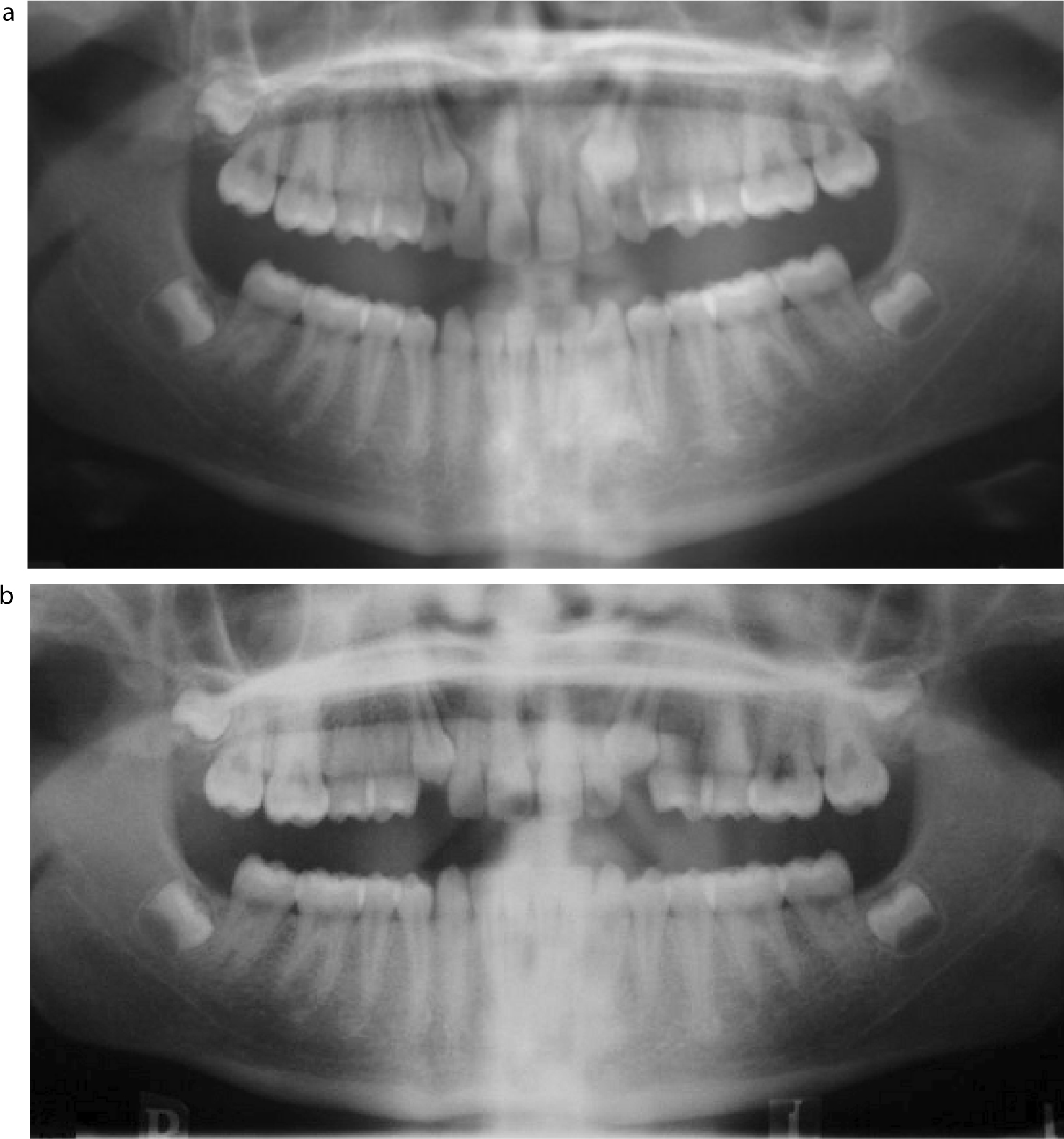

Resorption of the roots of the adjacent teeth is a more common consequence of aberrantly positioned unerupted teeth. Root resorption will only occur if the crown of the unerupted tooth is in close proximity to the adjacent tooth roots (ie in the line of the arch or close to it) and results from direct tooth contact rather than under pressure from an enlarging follicle.2 It occurs more commonly when the canine is closer to the midline and has advanced root formation.3 The incidence of resorption of lateral incisors, in the presence of palatally ectopic maxillary canines, is reported to be 12% on plain film4 (Figure 2). However, the incidence of root resorption being detected on CBCT ranges from 38% to 66%,5,2,6 as CBCT will permit a full 3D assessment of the lateral incisor roots. Resorption commonly occurs in the middle and apical thirds of the lateral incisor and is often classified as slight (<½ dentine thickness), moderate (>½ dentine thickness) or severe (pulp exposure). If no resorption has occurred by the age of 14, it is unlikely to occur.5 Resorption may lead to increased mobility of the adjacent teeth and hence be a clinical indicator of canine position.

If an aberrant canine tooth is causing resorption to either the lateral or central incisor, the long-term prognosis of the damaged tooth should be assessed, along with the chances of canine alignment. A tooth with extensive resorption may not have a good long-term prognosis and it may be prudent to sacrifice it in order to allow the canine to be aligned and camouflaged. If the canine is so far mesial that it has caused resorption of the central incisor, it is unlikely that alignment to the correct position will be successful. In this instance, the aberrant canine should either be extracted, or if resorption is extensive, aligned in the position of the central incisor and camouflaged (Figure 3). Alignment may possibly occur spontaneously if the resorbed tooth is extracted, or it may require active alignment with fixed appliances. It is not just aberrant palatal canines that can cause extensive root resorption of adjacent teeth, it can also occur with buccally positioned maxillary canines.7

Extraction of the ectopic canine

In instances where there is an unerupted upper or lower ectopic canine and extraction is indicated (Figure 4), it is important to be aware of potential surgical complications. Risks include swelling, bruising, post-operative paraesthesia, damage to adjacent teeth and bone loss during the extraction.8,9 There is little published literature reporting the incidence of damage to the roots of adjacent teeth during the removal of impacted canines. If the aberrant canine has caused resorption of an adjacent tooth, the crown will be in direct contact with the roots.2 Common sense dictates that the removal of such teeth will have increased risk of damage to the already resorbed adjacent tooth roots, due to their close proximity.

When the aberrant canine is extracted, the occlusion might be accepted, the space can be opened for prosthetic replacement or it can be closed, as in the case of the developmentally absent canine (see ‘Treatment for the developmentally absent canine’).

Alignment of the palatally placed canine

The vast majority of unerupted maxillary canines are palatally ectopic4 and The Royal College of Surgeons of England have developed guidelines dealing with the management of these teeth.10 Treatment will depend not only on the position of the ectopic canine, but also the age of the patient and his/her stage of dental development. Suggested treatment can range from simple interceptive extractions to surgical exposure of the canine and orthodontic alignment.

Interceptive extraction of the deciduous canine

Simple interceptive extraction of the deciduous canine, provided the ectopic permanent canine is favourably positioned, will hopefully result in successful eruption of the permanent tooth. This is reported to be successful in up to 80% of cases in the maxillary arch, provided sufficient space already exists.11 Power and Short12 found that, in the presence of crowding, only 62% of canines erupted, but a further 19% still improved position following interceptive deciduous extraction. The difference between these two studies highlights the importance of space being available for the unerupted canine (Figure 5). Although a Cochrane review concluded that there was no high quality evidence supporting the interceptive extraction of deciduous canines in such cases,13 a more recently published RCT has provided evidence supporting the practice of interceptive deciduous canine extractions.14

Interceptive extraction of the deciduous canine and space provision

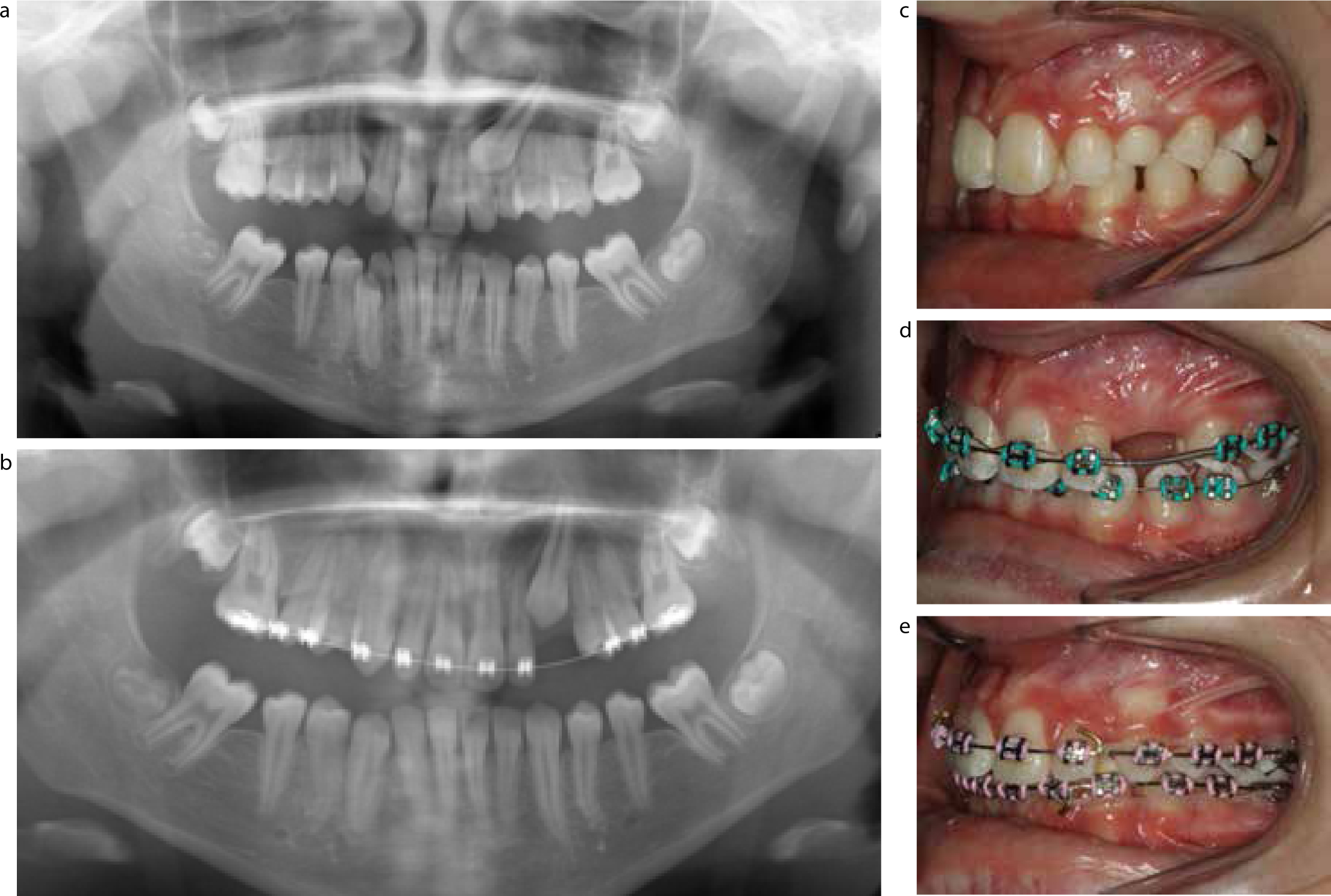

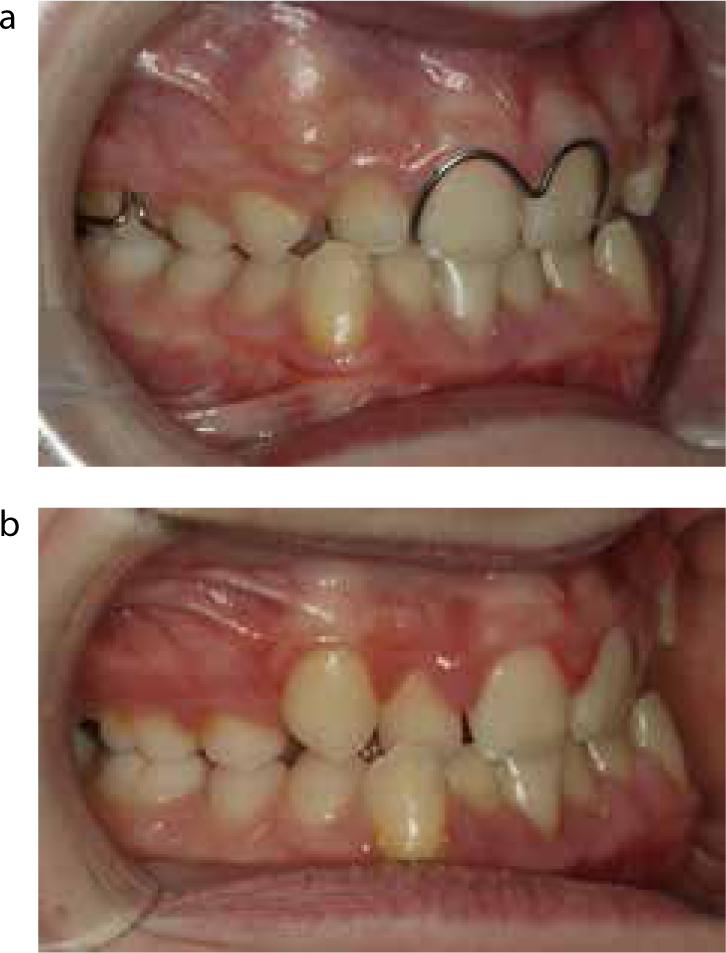

Power and Short12 highlighted the effect crowding has on the eruption of ectopic canines following deciduous extractions. There have since been several investigations into the effect of space provision on ectopic canine eruption. Olive15 used fixed appliances to provide space for the canine following interceptive extraction and found that 75% erupted into a mid-alveolar position, and nearly all improved in position. Baccetti and his co-workers16,17 used headgear to create space, also finding that a high proportion of ectopic canines successfully erupted into the arch. However, space gained through expansion did not significantly increase successful eruption rates when compared to the use of headgear,18 or even just a space maintainer.19Figure 6 illustrates a case where space was created for an aberrant maxillary canine, which subsequently erupted into the line of the arch.

Exposure and alignment of the ectopic canine

Surgical exposure and alignment of the ectopic canine may be indicated when interceptive measures fail, or the tooth is in such an unfavourable position to begin with that it is bound to fail to erupt. There are two main surgical methods of exposure of ectopic canine, namely the Open and the Closed techniques and these will be described first.

Open vs closed exposure

Open exposure technique20 (Figure 7) requires the surgeon to expose the crown of the unerupted canine, allowing the orthodontist to place an attachment directly on the tooth at a later date. Closed exposure21 (Figure 8) requires the surgeon to expose the crown of the canine, bond an attachment and gold chain and then replace the soft tissue flap. In this case, the orthodontist can then place traction to the chain at a later date.

Open exposure and direct visualization of the crown can aid the orthodontist in applying traction with an appropriate force vector to move it into the line of the arch, but this may be impractical if the tooth is very ectopic. Some clinicians favour early open exposure of the tooth in order to promote autonomous eruption and disimpaction before the placement of fixed appliances.22,23 However, if the exposure is insufficient, the mucosa may heal over the canine crown such that, by the time the patient returns to the orthodontist, there is no sign of the unerupted canine in the mouth. In the UK, open and closed exposures are undertaken with similar frequency.24

There are advantages and disadvantages of both techniques, as discussed by Mathews and Kokich23 and by Becker and Chaushu25 and these are summarized in Table 1. A Cochrane review in 200826 concluded that there were no studies comparing open and closed exposure that could be included in the review and therefore there was an insufficiency of evidence. As a result, the same author conducted a trial comparing open and closed exposure and reported that there were no differences in surgical outcome, operating time or patient-related outcome measures (PROMs)27 between the two techniques. Nor were there differences between the techniques in terms of the final periodontal condition of the exposed canines28 and whether orthodontists could identify which technique was used, although they could identify an exposed tooth.29,30,31

| Open Exposure | Closed Exposure | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | May reduce total time with fixed appliances |

Follicle can remain and influence movement |

| Disadvantages | May be sore or require coverplate |

Force vector applied to tooth ‘blind’ May drag tooth along root surfaces |

Alignment of the canine following exposure

Whatever method of exposure is carried out, the task of alignment of the canine still remains. The root surface area of the canine is substantial32 and therefore movement of this tooth is anchorage demanding, both vertically and horizontally.

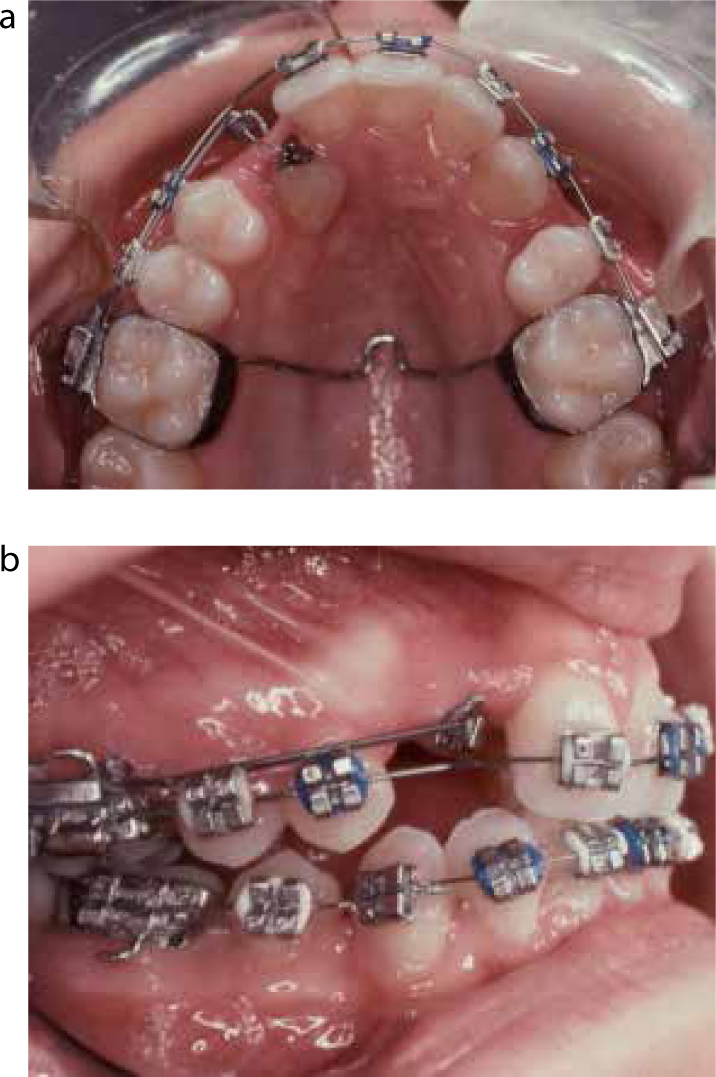

Occasionally, the ectopic canine may be the only substantial feature of the patient's malocclusion. In these instances, traction can be applied to the exposed canine using a sectional TMA archwire attached to a transpalatal arch33 (Figure 9), in the case of the upper, or a lingual arch, in the case of a lower. This will allow majority of tooth movement required to align the canine without the need to place an appliance on the rest of the teeth. Once brought to the dental arch, finishing can be achieved with a full fixed appliance. Alternatively, in the upper arch an upper removable appliance can be used to apply vertical traction to the canine and, once it is in the mouth, a fixed appliance can be fitted to fully align the tooth and treat the rest of the occlusion (Figure 10).

If a fixed appliance is required for correction of other features of the malocclusion, or to create space, alignment of the aberrant canine can be performed, either with a ballista spring,34 elastic chain or ligature (Figure 11) or a nickel titanium (NiTi) sectional archwire ‘piggy back’ (Figure 12). The use of a NiTi wire or ballista spring will have the advantage of providing relatively constant force to the canine compared to elastic, which will experience significant force decay.35 Once aligned, the canine may require labial root torque to restore the canine eminence and create a good gingival margin.

Alignment of the buccally placed canine

If the canine tooth is unerupted and palpable buccally, its failure to erupt is most commonly due to insufficient space, however, these crowded teeth often erupt high in the buccal sulcus (Figure 13). In such cases, when the canine cusp tip is mesially positioned and the tooth is also mesially angulated, extraction of the first premolar will often allow the canine to drop down spontaneously into the line of the arch. As part of this treatment it may be necessary to fit a fixed or removable space maintainer (Figure 14). If the canine is distally angulated, it is unlikely to improve a great deal following the premolar extraction, and correction with fixed appliances will be required. If significant root translation is necessary, this can be extremely anchorage demanding. If there is already good contact between the lateral incisor and the first premolar, extraction of the canine may well be the treatment of choice.

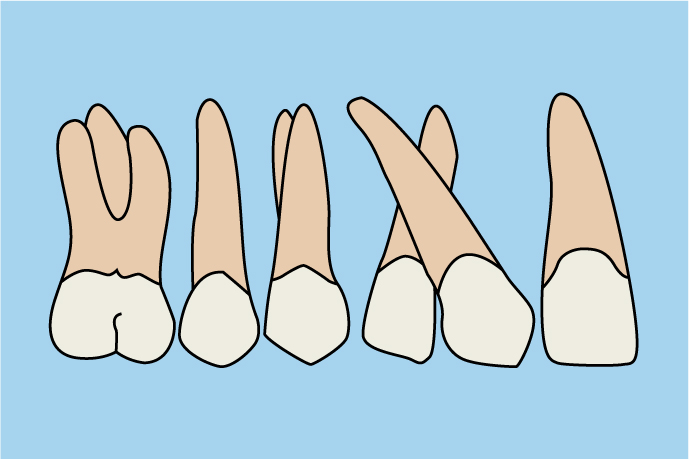

Treatment of the transposed canine

A transposition can either be a true transposition, where the whole tooth is transposed with the adjacent tooth (Figure 15), or a pseudotransposition, where only the crown is in the wrong place, with the root being in the correct position within the line of the arch (Figure 16). Whereas a pseudotransposition is often amenable to orthodontic treatment, a true transposition can usually only be treated following the extraction of the transposed canine, or the adjacent tooth. This is because it would otherwise require movement of the transposed canine out of the alveolus and around the adjacent tooth. Extraction of the transposed tooth is often the treatment of choice in the crowded dentition and, in the uncrowded dentition, it may be wise to accept the transposition.

Treatment duration

On average, patients with bilateral impacted canines take 10 months longer to treat than orthodontic patients who do not have impacted canines.36 In the case of impacted canine patients, the average length of treatment is slightly greater than 2 years.36,37 Other factors that might increase treatment duration in such cases include the severity of the impaction and the age of the patient.38 This is perhaps supported by the finding that only 70% of adults with impacted canines are successfully treated when compared to a matched group of children.39 This may be due to ankylosis of the canine teeth and can occur in one third of patients referred for failed eruption of aberrant canines.40 Ankylosis of canine teeth following exposure is more likely with increased patient age, depth of impaction and a closed exposure technique,41 but is not completely predictable.

Conclusion

Eruption of the canine is a significant milestone in dental development. Often this occurs without incidence, but the aberrant canine can be one of the most challenging treatment scenarios commonly faced by the orthodontist. Early detection and interceptive treatment for aberrant canines can reduce the risk of adverse events, such as resorption, and the complexity of definitive treatment. Clinicians should be aware of the possible sequelae of unerupted canines and the management strategies.