References

A concealed central giant cell granuloma and its combined orthodontic and surgical management

From Volume 11, Issue 2, April 2018 | Pages 74-75

Article

Central giant cell granulomas (CGCGs) are benign, intraosseous lesions of the jaws which are typically painless.1 The lesions account for less than 7% of benign lesions found in the jaws,2 most commonly occurring in the anterior mandible and in women under 30 years of age.3 CGCG incidence in the general population is 1.1 people per million, with the peak incidence between 10 and 19 years.4

Histologically, they consist of a fibroblastic stroma with spindle-shaped cells displaying a high mitotic rate, multiple foci of haemorrhage, plus aggregations of prominent multinucleated giant cells.5 Radiographically, they can be small, unilocular and slow growing, or large, multilocular and aggressive with mass effect on adjacent structures causing bony expansion, root resorption and tooth displacement.3,6 The primary treatment option remains to be surgical management with either curettage or block resection.7,8 Other management options include systemic calcitonin injection9 or the injection of intralesional corticosteroids.10,11

A case that delayed presentation due to ongoing fixed appliance treatment which masked classic symptoms of malocclusion and tooth mobility is presented. The patient's appliance later aided in the joint management approach of surgery and orthodontic stabilization during the post-operative healing period.

Case report

A 13-year-old girl was urgently referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery of a district general hospital by her orthodontist. The patient was undergoing fixed appliance therapy for a crowded dentition beginning 8 months previously. At her most recent appointment for changing the active wire, a large swelling was noted in the incisor, premolar and molar region of the left side of the mandible, with excessive mobility of the anterior and premolar teeth when the orthodontic wire was removed.

On referral to hospital, clinical examination revealed a firm intra-oral swelling with bony expansion of the buccal and lingual symphysis and left body of the mandible. The lesion was not painful nor was there paraesthesia in the mental nerve distribution. All teeth were vital. The patient was fit and well with no pre-existing medical conditions.

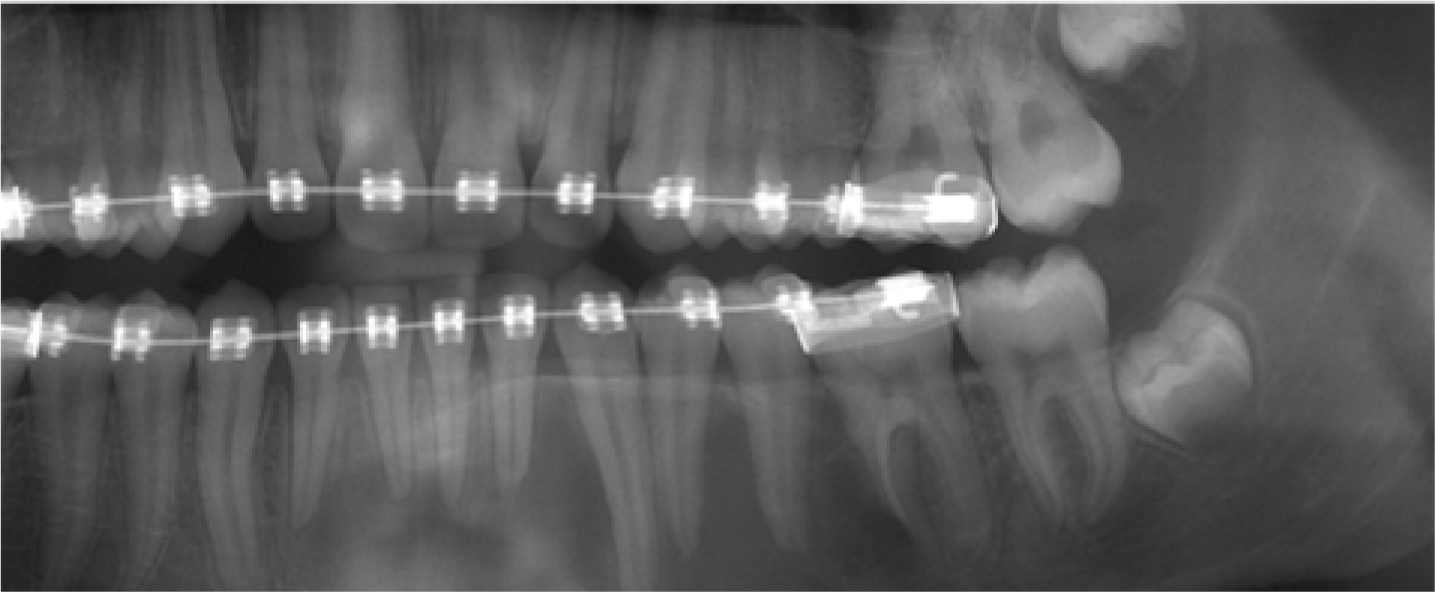

A panoramic radiograph revealed a large, multilocular radiolucent lesion extending from the lower right lateral incisor to the lower left first molar (Figure 1). There was displacement of the teeth involved in the lesion and clear root resorption of the lower left lateral incisor and the mesial root of the lower left first molar tooth. A previous panoramic radiograph taken before commencing orthodontic treatment showed no abnormality in the area.

The provisional diagnosis was of a giant cell tumour of bone favouring a central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) due to the radiographic appearance and position of the lesion in the anterior mandible in a young, female patient. An incisional biopsy under local anaesthetic confirmed the diagnosis.

In the authors' experience, full resolution can be achieved with surgical curettage. After discussion with the patient and her family, it was decided to proceed with surgery, after requesting the placement of a passive, rigid stainless steel wire to stabilize the dentition prior to surgery.

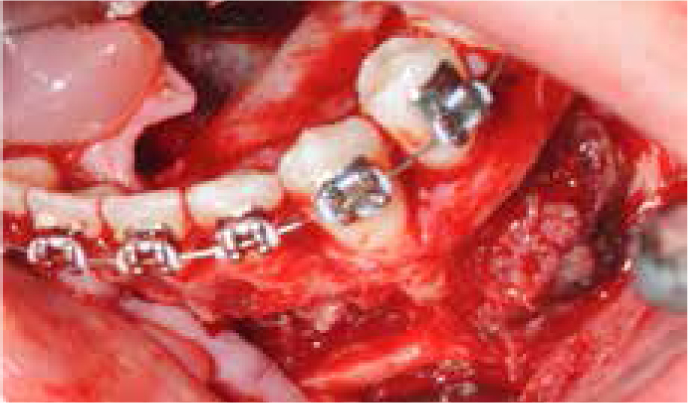

Curettage of the lesion was performed under a general anaesthetic. Clinical photography demonstrates the extent of the lesion which had perforated both the buccal and lingual plates in some areas (Figures 2 and 3). The patient was placed on a strictly puréed diet and her rigid orthodontic wire remained in place post-operatively.

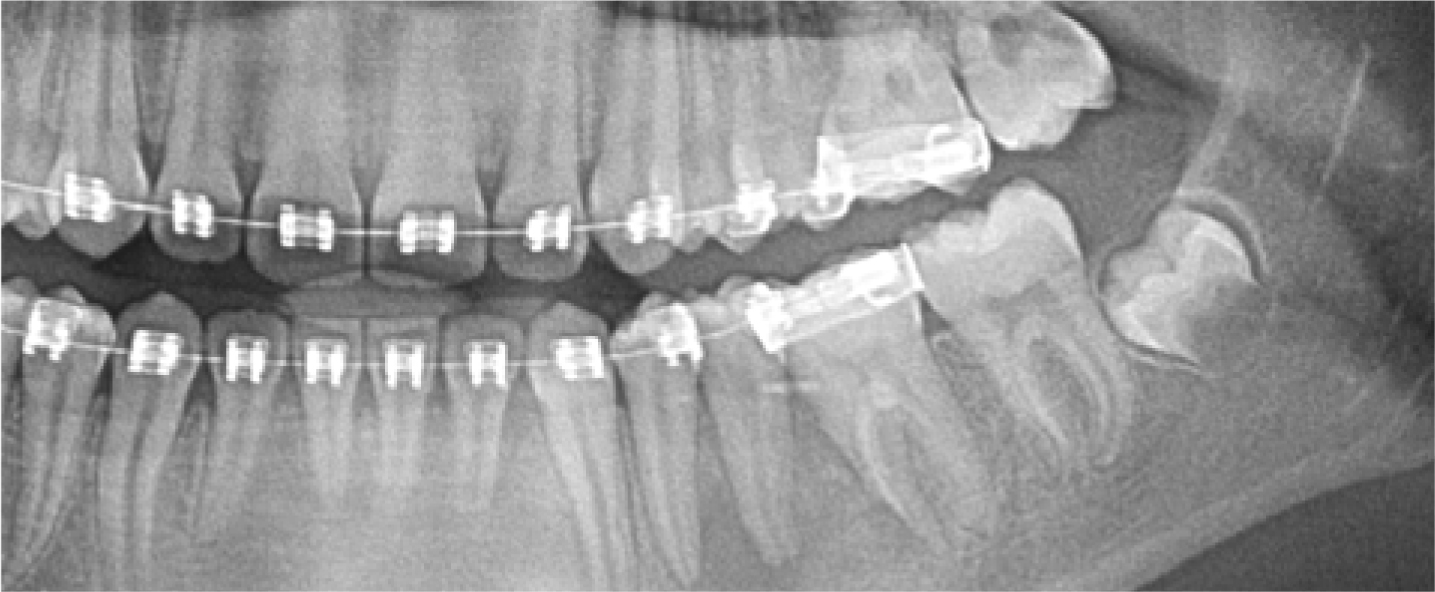

At post-operative review the patient remarkably had no mental nerve paraesthesia. At 4 months a panoramic radiograph showed excellent bony infill with the radiolucent area reduced significantly in size (Figure 4). The teeth were stable and the active orthodontic treatment was re-commenced.

Discussion

Because the patient was undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliance therapy, the large CGCG grew un-noticed. These lesions can be fast growing and aggressive, leading to rapid expansion and hypermobility of teeth. However, lesions can also be slow growing and behave less aggressively1,3,6 and are more likely to present later.

The patient's orthodontic treatment masked any tooth displacement or associated potential malocclusion, and lesions classically do not cause pain. Due to root resorption and root displacement visible radiographically, it is more likely that this is a CGCG of an aggressive type.

Whilst orthodontic treatment delayed the presentation of the lesion, it did however stabilize the dentition pre- and post-operatively. On discovery of the lesion, the fixed appliance in the lower arch acted perfectly as a splint with a passive, rigid wire during surgical management and post-operative recovery until adequate bony infill was demonstrated.

In this case, the diligence of the patient's orthodontist led to rapid referral and initiation of the combined management of this large CGCG. This case highlights the importance of routine soft tissue examination at an orthodontic appointment, not just at regular dental check-ups. The nature of visits being more regular, in comparison to visits to a patient's general dental practitioner, means pathology can often be recognized earlier, which could lead to a better outcome.